This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Art Deco Jewellery

Art Deco jewellery is attractive for us today for its simplicity of line, shape, abstract form. It can equally be luxurious or sumptuous.

Its roots in Modernism evoke a more refined age – an imagined world of Agatha Christie’s Poirot with golden interiors, gleaming white exteriors and sophisticated soirees. It is the world of the Roaring Twenties.

One of the Art Deco rings at Goodwins

In jewellery, the most luxurious of the arts, it was a significant time of aesthetic change.

Covering the whole of Art Deco jewellery, a time spanning from perhaps 1910 to 1939, isn’t possible in one article. This is the first in a series of articles on the period.

In this opening article we will look at key influences on Art Deco, the link of jewellery with fashion, and the 1925 Paris International Exhibition that showcased key jewellery designers of the age.

What is Art Deco?

If you were to walk into an Edinburgh jewellers in the 1920s and ask to see an Art Deco ring, they would give you an inquisitive look.

In fact you could ask the same question in London, New York and even Paris but no-one would know what you wanted.

The term Art Deco was coined in the late 1960s to describe a particular decorative style that has its roots in Art Nouveau, abstract and primitive art as well as many other sources.

Art Deco encompasses many applied decorative arts, including sculpture, product design, architecture, fashion and of course jewellery.

Where did Art Deco come from?

The Art Deco period is often thought to be the interwar years – most of the decades 1920 to 1940. However the style comes from 1905 onwards, the end of the Art Nouveau movement.

Art Nouveau’s iconic works is visually familiar to us. We can think of Gustav Klimt’s sumptuous, romantic paintings in the galleries of Vienna. There are Hector Guimard’s fluid iron work in the Metro stations of Paris and Gaudi’s spectacular architecture in Barcelona.

One of Hector Guimard’s Metro stations in Paris – an iconic example of the Art Nouveau style. Photo: Moonik – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Art Nouveau was in itself a reaction to the stuffiness of the late Victorian period. There is an idea that Art Deco was then a reaction against Art Nouveau.

However some art historians say it can be seen as a logical progression. Style moves from the fluid form of handmade crafts to the geometric forms of the Modernists. While jewellery was to be known for geometry, there was still a characteristic curvature to Art Deco furniture, interior design and architecture.

When thinking about Modernism, it’s worth considering where that movement came from. In part it was derived from the Italian Futurists and the geometric fracturing of planes of the Cubists. For Art Deco fashion, the main painterly influences were Picasso, Braque and Gris.

Cubism and Art Deco

The Cubists are known for being primarily influenced by African tribal art.

Cubism, however, is the prime cause of fashion’s modern forms. It brought flat planes and angles where before there was a deliberate aesthetic to accentuate the female form.

Fashion left behind the bold silhouette of the Belle Epoque. Instead it substituted it with a soft cylinder that doesn’t describe the body within.

Richard Martin suggests that,

‘It was not the art of Cubism per se but the culture of Cubism that influenced fashion, just as the culture of Cubism might be said to align it with new ideas in theatre, literature, and eventually, the movies.’

Simultaneous Windows on the City by Robert Delaunay – flickr, Public Domain

Cubism was art for all, not for a select few. This is ironic given that it is less accessible to many now than the realist art that preceded it. Its influence on fashion, towards planes and geometry, made jewellery more accessible with a desire for new materials.

As an example, Chanel’s geometric designs of the mid-to-late 1920s can be likened to the interlocking collages of Braque or Picasso from a decade earlier.

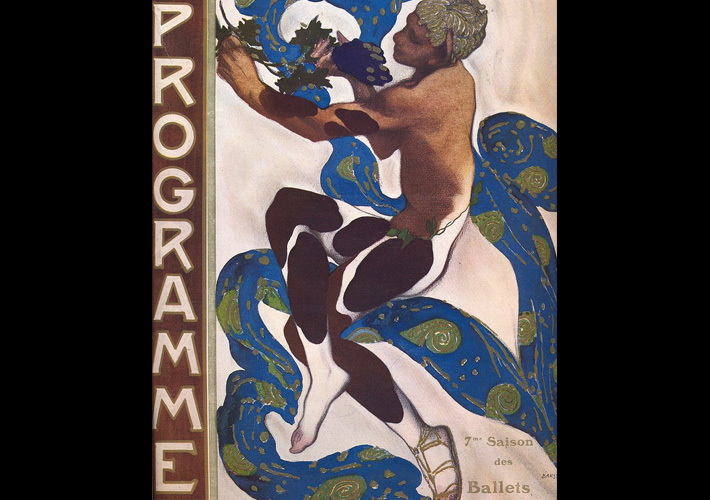

The Ballets Russes

Public Domain, Programme for Ballets Russes by Leon Bakst

The cross-over period between Art Nouveau and Art Deco was epitomised by the Ballets Russes (Russian Dance) – a dance company founded by the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev in 1909.

It included collaborations between dancers, choreographers, designers, composers, musicians and artists.

Debussy, Prokofiev and Stravinsky contributed at the same time as Matisse and Picasso. Costumes were designed by Leon Bakst and Coco Chanel.

The avant-garde creations in the ballet of the pre-war, pre-Revolutionary years were to directly influence the fashion of the 1920s.

Art Deco fashion

We can’t look at Art Deco jewellery without looking at Art Deco fashion. Jewellery is worn to complement clothing and is a fashion statement in itself.

To appreciate the changes in jewellery from the Edwardian period to the 1920s one has to consider the change in fashion.

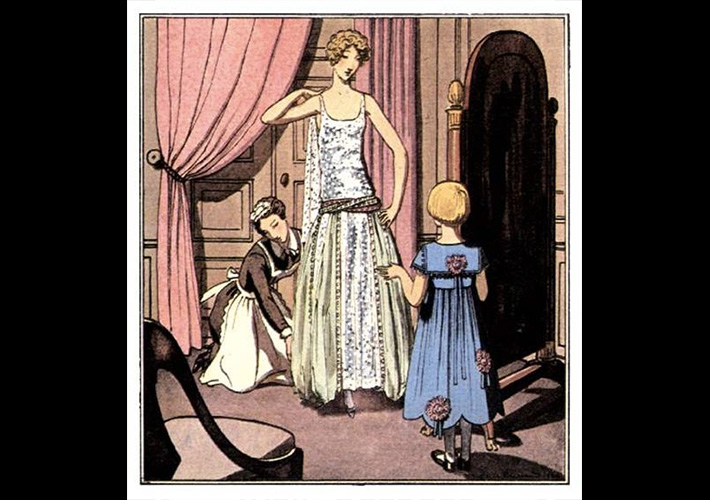

Photo: Pierre Brissaud – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Ladies’ fashion in the 1920s was radically different to what was worn, or even deemed acceptable, before the war.

Curves and frills were out.

Simplicity was in.

As always, Paris was the key source of Art Deco fashion – in fact, the home of all the decorative arts that we think of as being part of Art Deco.

The status of fashion – or couture – as an ‘eighth art’ was exceptionally important to France – women’s clothing accounting for 2.5 billion francs of exports in 1924. The quality of the art reinforced by a ‘name’, what we’d refer to as a brand today.

‘Paris, to the average woman, means primarily clothes. Clothes and style. The names and creations of Parisian clothes are familiar to her also. She knows about Worth and Lanvin and Paquin. In the fashion pages of magazines she has seen the names of Jenny and Vionnet. These are the names that thunder an imperious authority in America and throughout the rest of the world too.’

A new age and a simplified look

It was in this atmosphere, this pre-eminent position as the global leader in fashion, that couturier Paul Poiret transformed dress design. He wrote:

‘It is unthinkable for the breasts to be sealed up in solitary confinement in a fortress-castle like the corset, as if to punish them’.

His designs freed the female figure and rejected superfluous ornamentation, allowing for more comfort.

Poiret introduced the long, sleeveless tube, the lean look we think of as a 1920s dress.

Hemlines and the back of the dress fluctuated up and down, but the plunging necklines offered scope for dangling necklaces, sometimes so long as to be draped over a shoulder or wrapped around an arm.

The tunic dress – with a hemline around the top of the knee as it was in 1925 – and a long necklace, were the fashion symbols of the age.

A simplified silhouette allowed jewellery designers to adorn any bare surface. There was a renaissance of necklaces with pendants, strings of pearls, bracelets, and the introduction of watch straps – a novel addition to a woman’s wardrobe. A leather strap was worn by day, a jewelled strap during the evening.

With no more gloves – that staple of Edwardian fashion – hands were free for rings of all shapes and sizes.

The rule book had been thrown out and a new one was being written. The new rule was that there were no rules.

In all fashion, the magazines of the time, Tatler, Vogue and La Gazette du Bon Ton, led consumer desire for greater comfort and ease of movement. The streamlined dresses were made with looser, lightweight materials, which was then echoed in the jewellery.

Influences on Art Deco jewellery

While the cut of the dresses were as simple as possible, the fabrics were often rich patterns influenced by exotic subject matter. The fashion world turned to the Persian and Oriental motifs used by the designers of the Ballets Russes.

Fashion led – and jewellery followed.

China

Chinese influences led to the use of exotic materials outside the normal palette for jewellers. Jade, onyx, coral and amber were used where previously only diamonds and other precious stones would do.

Tutankhamun’s scarab pectoral piece, discovered in 1922

Photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbera CC BY 2.0

Egypt

The discovery in 1922 of the tomb of Tutankhamun by Sir Edward Carter had a major influence on jewellery. The world went Egypt crazy.

The discoveries were photographed and widely reported across the world (as in the piece pictured above). Soon hieroglyphs and Egyptian symbols were making their way into decorative pieces.

In 1924 Van Cleef & Arpels were incorporating eagles and lions into bracelets of rubies, sapphires, emeralds, diamonds, onyx and platinum. These were to become common themes in art deco jewellery.

Africa

Jean Dépres used crystal, silver and gold in geometric patterns from tribal African masks. If it was exotic, it was a source of inspiration.

It’s probably a misconception that Art Deco is purely about geometry. Angles, simple shapes and symmetrical designs are used to apply the exotic influences to the piece.

There is no single aesthetic. The jewellery in the Age of Elegance doesn’t fit into one simple classification.

This was true of most of Art Deco art and design; not sparse or pared back, but lavish and luxurious.

Photo: Elee46 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

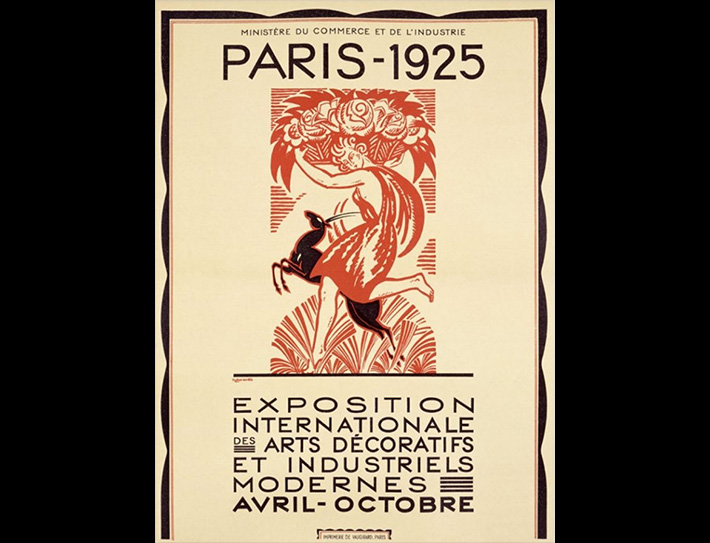

The 1925 Paris International Exhibition

‘France owes it to herself to prove to the word that her artists, craftsmen and manufacturers have not lost their innovative ingenuity, the quality of balance and logic, especially allied to gifts of grace and fantasy, that have earned her, in the past, a universal sovereignty surer and more durable than that which flows from the power of arms.’

The Paris 1925 Exhibition was the defining moment of what we know as the Art Deco style. As is the way with international exhibitions, it was also the catalyst for the spread of the style.

It was dedicated to modern ‘decorative’ or applied arts unlike the Paris World Fair of 1900.

France was seen as a leader of taste and producer of luxury goods and as the centre of the world of fashion. It sought to demonstrate this in the exhibition of 1925, much delayed after the initial proposals in 1907.

After the Great War, modernity and modernisation became the driving factors behind the exhibition.

Photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from Paris, France – 1925, quand l’Art déco séduit le monde (Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine, Paris), CC BY 2.0

Art Deco Jewellery at the 1925 Paris Exhibition

France’s luxury goods industries were a powerful symbol for France as a whole. Their supremacy provided focus for resuming preparations for the exhibition.

While other nations, including Britain and Italy, were present, the feared German resurgence didn’t materialise and Germany was conspicuous by its absence from the exhibition.

The USA, an economic powerhouse and saviour of Europe in 1917-18, was offered a prime site but didn’t attend with the belief that ‘there was no modern design in America’. This of course wasn’t strictly true, but was regretted on both sides of the Atlantic.

Modern inspiration and real originality

Modernism was the key to all design at the exhibition. In fact the Exhibition demanded that all exhibits should demonstrate “a modern inspiration and a real originality’. Henry Wilson, a British jeweller, wrote this report of the French jewellery shown at the Paris 1925 exhibition:

‘There was very much that was new in the French Section of Jewellery, and much that was very beautiful. Jade, black onyx and enamel were freely used to give contrast and richness.

Rainbow effects of the prismatic colours natural to coloured gems were much sought after, and the combinations in most cases were rich and beautiful.

In fact, colour was being sought instead of mere brilliance. In addition to this there was a tendency towards oriental effects in design. [It was] derived possibly from the use of oriental carved stones as centres of ornament.’

Cartier and the Style Moderne

Wilson was referring in part to Cartier’s shoulder necklace incorporating three huge carved Mughal emeralds, with a matching diadem and brooch.

If one were to look for a piece that expressed the high point of Art Deco jewellery, this was it.

Pearls, diamonds and black enamel linked the emeralds – set in hinged sections draped across the front of the mannequin. Strips of the same eye-catching materials hung down the back. Although stunning, Wilson doubted it could be worn and ultimately it wasn’t sold.

Cartier also showed black and white jewellery of diamonds and black onyx – the monochrome combination having been fashionable since before the Great War.

The contrast of the artificially stained onyx with the pavé diamonds was a key moment in the rise of what we can now identify as Art Deco costume jewellery.

In fact Cartier set itself apart, not content to show their work alongside the other jewellers in the main Grand Palais, but featuring among the fashion houses in the Pavillon de l’Élégance.

“A dizzying array”

Although set apart from the competition, nestled in with the high fashion of the Exposition, Alastair Duncan says there was a “dizzying array of jewellery, including ear clips, bracelets, tassel pendants, necklaces, fibula brooches, jabot pins, chokers and stomachers”.

He goes on to indicate the variety of influences on the new decorative style:

‘Islamic art – stars and geometrical themes derived from carpets. Chinese art – dragons, chimeras, pagodas and Buddhas. Egypt – Tutankhamun-like temples, hieroglyphics, sphinxes, scarabs, lotuses and sarcophagi. As well as the prevailing “high-style” Art Deco of baskets of fruits and flowers in carved gemstones.’

The Egyptomania also inspired winged female figures, falcons and lotus flowers with the combinations of green (emerald), red (ruby), blue (sapphire), black (onyx) and white (diamond).

Louis-Francois Cartier was so enthusiastic about the art of Egypt that he occasionally made contemporary works around antique pieces brought back from digs in the desert.

Other Art Deco jewellery designers at the exhibition

Back in the Grand Palais, Georges Fouquet – chairman of the jewellery exhibition – and his son Jean Fouquet displayed work in a more Modernist style.

Georges used platinum and diamonds in pendants with rock crystal and onyx. Jean placed an emphasis on metals – white and yellow gold, platinum and lacquered silver. Jean also used purer geometrical shapes: squares, circles, triangles and pyramids.

Modernism was deliberately represented based on the selection of thirty distinct displays from a blind competition of nearly four hundred entries.

Exhibitors included not just the Fouquet company but Chaumet, Dusausoy, Lacloche Frères, Linseler & Machack, Boivin, Mauboussin, Mellerio, Ostertag and Van Cleef & Arpels.

Artist-jewellers Raymond Templier, Paul-Émile Brant and Gérard Sandoz produced pendants, bracelets and brooches in new materials. These included platinum, onyx and chromium-plated metal.

Després

While many were making luxury objects, Jean Després believed that jewellery should be inspired by contemporary aesthetics. In 1925 that meant industrial design. During the war Després had worked in a military workshop that manufactured aeroplane engines. He brought his interest in cold precision to jewellery and presented flattened silver necklaces.

Van Cleef & Arpels

Van Cleef & Arpels was a jewellery house founded by families of diamond merchants in 1906. They took haute joaillierie, literally high jewellery, to new heights. At the 1925 Exposition, Van Cleef & Arpels won a grand prix for one of its jewellery designs – a half-open rose in diamond-studied rubies and emeralds.

In conclusion, with so many exquisite designs, the 1925 Exposition was indeed the high point of ‘high-style’ Art Deco in French jewellery. It proved a success not just for French luxury industries, but also in disseminating the Art Deco style around the world.

—

In the next article we’ll be examining the use of new materials and styles in Art Deco jewellery.

Bibliography

Avery, Derek Art Deco, Chaucer Press, 2004

Benton, Charlotte & Phillips, Clare Art Deco 1910-1939, V&A Publications, 2003

Duncan, Alastair Art Deco Complete, Thames & Hudson, 2009

Gallagher, Fiona Christie’s Art Deco, Pavilion Books, 2000

Martin, Richard Cubism & Fashion, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998

Miller, Judith Art Deco, Dorling Kindersley, 2005